Introduction

Human connection is at the heart of emotional well-being. From the very first days of life, a child depends on caregivers not only for food and shelter but also for warmth, trust, and safety. Through this bond, children learn to navigate relationships, understand boundaries, and differentiate between safe and unsafe environments. When these early bonds are disrupted, however, serious difficulties in social and emotional development can emerge.

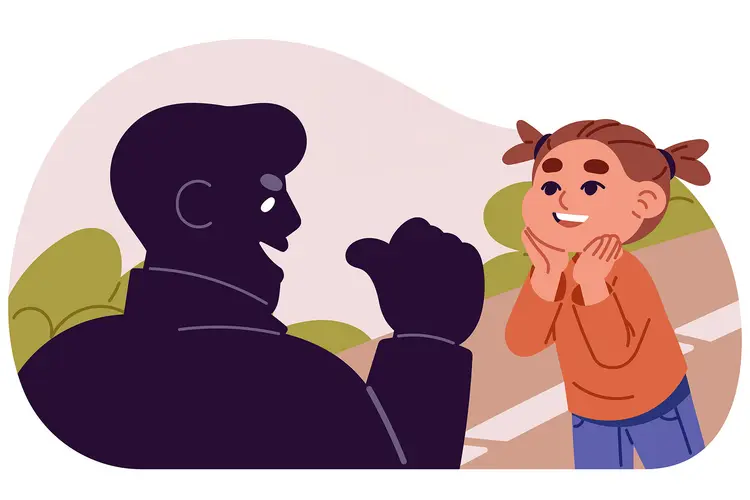

One condition that reflects this disruption is Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (DSED). While it might initially appear that a child with DSED is unusually friendly, affectionate, or outgoing, these behaviors mask a deeper challenge. Instead of forming selective, secure attachments, the child shows little hesitation in approaching unfamiliar adults, lacks a sense of danger, and often struggles with healthy boundaries.

Understanding DSED is important not only for clinicians but also for caregivers, teachers, and even the individuals who grow up with the condition. This disorder can have long-lasting effects, influencing relationships well into adulthood if left untreated. In this article, we will explore DSED in depth—what it is, how it is diagnosed, how it differs from Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD), what it looks like in adults, and how treatment can help foster healthier connections.

What is Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder?

Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder is a rare but significant condition that typically emerges in early childhood. At its core, it involves a pattern of culturally inappropriate, overly familiar behavior with strangers. Children with DSED do not show the natural caution that most children display around unfamiliar people.

Key features of DSED

- Overly familiar behavior: Children may hug, sit with, or hold hands with strangers without hesitation.

- Indiscriminate social interactions: They may fail to show a preference for familiar caregivers, treating all adults as equally safe.

- Lack of checking back: In new or stressful settings, most children periodically glance back at their caregiver for reassurance. Children with DSED often don’t.

- Overtrusting behavior: They may accept food, comfort, or invitations from people they have just met.

These behaviors are not simply a sign of being “friendly” or “social.” Instead, they reflect serious disruptions in attachment, usually stemming from neglect, inconsistent caregiving, or institutional upbringing.

Developmental background

DSED typically develops in contexts where children have not had the chance to form stable attachments. Common situations include:

- Institutional care with rotating caregivers.

- Severe neglect during early years.

- Frequent changes in foster care placement.

- Caregiving environments marked by abuse or emotional unavailability.

Without consistent caregiving, children do not learn the basic trust that normally forms the foundation of social development. Instead of distinguishing between safe and unsafe people, they may treat all adults as interchangeable, leading to the hallmark signs of DSED.

What are the DSM-5 Criteria for Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder?

The DSM-5 provides specific guidelines for diagnosing DSED to distinguish it from typical sociability or other conditions.

DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for DSED

According to the DSM-5, the following must be present:

- Pattern of behavior with unfamiliar adults that includes at least two of the following:

- Reduced or absent reticence when interacting with unfamiliar adults.

- Overly familiar verbal or physical behavior that is not culturally appropriate.

- Diminished or absent checking back with an adult caregiver after venturing away in unfamiliar settings.

- Willingness to go off with an unfamiliar adult with minimal or no hesitation.

- The behaviors are not limited to impulsivity (as might be seen in ADHD) but reflect disinhibited social behavior.

- The child has experienced a pattern of extreme insufficient care, such as:

- Neglect of basic emotional needs for comfort, stimulation, and affection.

- Repeated changes of primary caregivers that prevent stable attachment.

- Rearing in institutions with limited opportunities for stable attachment.

- The child has a developmental age of at least nine months.

- The symptoms are present for at least 12 months to confirm persistence.

Why the criteria matter

These criteria ensure that clinicians can differentiate DSED from simple extroversion. A child who is naturally outgoing might enjoy meeting new people but still shows a healthy awareness of boundaries. In contrast, a child with DSED demonstrates indiscriminate trust and attachment behaviors that can place them at risk.

What is the Difference Between DSED and RAD?

Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (DSED) and Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) are both attachment disorders linked to early neglect or disrupted caregiving. However, they present in very different ways.

Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD)

- Children with RAD are withdrawn, inhibited, and emotionally unresponsive.

- They show little or no interest in forming attachments, even with caregivers.

- Often appear emotionally flat, untrusting, or detached.

Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder (DSED)

- Children with DSED are overly social, outgoing, and indiscriminate in their interactions.

- They actively seek comfort and attention but from anyone, including strangers.

- They lack normal social boundaries and can be excessively affectionate.

Key comparison

| Feature | RAD | DSED |

|---|---|---|

| Attachment style | Inhibited, withdrawn | Indiscriminate, overly familiar |

| Social behavior | Avoids comfort, emotionally distant | Seeks comfort from anyone |

| Risk | Emotional detachment, isolation | Overtrust, lack of caution with strangers |

| Cause | Severe neglect, trauma, lack of caregiver responsiveness | Severe neglect, unstable caregiving, institutional rearing |

In short, RAD represents too little attachment, while DSED represents too much indiscriminate attachment.

What Does DSED Look Like in Adults?

Although DSED is most commonly diagnosed in children, its effects can continue into adulthood if untreated.

Common traits in adults with a history of DSED

- Difficulty with boundaries: May share personal details too quickly or trust others without hesitation.

- Relationship struggles: Overly intense or unstable relationships due to lack of healthy attachment models.

- Impulsivity in social settings: Engaging in risky interactions, trusting the wrong people, or becoming overly dependent.

- Challenges with intimacy: Confusion between closeness and overfamiliarity, leading to strained personal connections.

- Emotional vulnerability: Adults may be more likely to experience exploitation or disappointment.

Real-life examples

- An adult who quickly forms friendships but often feels hurt when others do not reciprocate the same level of trust.

- Someone who overshares with strangers, later regretting their openness.

- A person who struggles with long-term stable relationships, cycling through intense but short-lived connections.

While DSED in adulthood is not formally recognized as a separate diagnosis, these patterns highlight the lasting impact of early attachment disruptions.

Causes and Risk Factors of DSED

The development of DSED is almost always linked to early caregiving environments.

Main causes

- Severe neglect – lack of emotional nurturing, affection, or consistent attention.

- Institutional care – children raised in orphanages or group homes with rotating caregivers.

- Multiple foster care placements – frequent changes prevent the formation of secure attachments.

- Abuse and trauma – exposure to unsafe caregiving environments.

Risk factors

- Early separation from primary caregivers.

- High caregiver turnover.

- Living in environments with little stimulation or social interaction.

- Cultural or social settings where children are denied stable emotional support.

How is DSED Diagnosed?

Diagnosing DSED requires careful clinical evaluation.

Diagnostic steps

- Clinical interviews with caregivers to gather history.

- Behavioral observation of how the child interacts with familiar and unfamiliar adults.

- Developmental assessment to rule out autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, or other conditions.

- Use of DSM-5 criteria to confirm persistence and context of symptoms.

Because DSED can resemble other issues—such as natural extroversion or impulsivity—thorough assessment is critical.

Treatment and Management of DSED

Treatment for DSED focuses on creating a stable, nurturing environment and addressing the child’s emotional needs.

Core interventions

- Attachment-focused therapy: Helps build trust and secure connections with caregivers.

- Play therapy: Provides a safe space for children to express emotions.

- Family therapy: Supports caregivers in learning how to provide consistent emotional responses.

- Parent training: Helps caregivers develop skills to create structure, warmth, and predictable routines.

Importance of stability

The single most important factor in treatment is stable caregiving. A consistent, loving environment allows the child to gradually learn healthy boundaries and trust.

Prognosis

With early intervention, many children with DSED improve significantly. However, without treatment, difficulties may persist into adolescence and adulthood, increasing vulnerability to risky relationships and emotional struggles.

Living with DSED: Stories and Examples

Living with DSED can be challenging not just for the child but also for caregivers and loved ones.

For children

A child with DSED might eagerly run into the arms of a stranger at the park, appearing friendly but raising safety concerns. Teachers may notice the child seeks attention from any adult, often disrupting class to connect.

For caregivers

Parents may feel conflicted—appreciating their child’s friendliness but worrying about their safety and lack of caution. Caregivers often need support to manage the unique challenges of DSED.

For adults

Adults with unresolved DSED may find themselves in unbalanced friendships, workplace conflicts, or unhealthy romantic relationships. Awareness and therapy can help them build healthier patterns.

Conclusion

Disinhibited Social Engagement Disorder is a complex condition rooted in early caregiving disruptions. While children with DSED may appear friendly and affectionate, their lack of boundaries signals deep challenges in attachment. Recognizing the signs early, understanding the DSM-5 criteria, and distinguishing it from conditions like RAD are essential steps toward providing the right support.

Treatment focuses on building stability, trust, and secure attachments. With consistent caregiving and therapeutic intervention, children with DSED can learn to form healthy relationships and navigate the world more safely.

Even in adulthood, when DSED-related traits may persist, understanding and therapy can help individuals build resilience and healthier connections. At its core, healing from DSED is about restoring what was disrupted in early life—the ability to trust, connect, and love in safe and meaningful ways.