Congenital anomalies are a broad category of birth defects originating in the womb that affect the structure or function of the body. Major structural irregularities are typically the emphasis for practicality and efficiency reasons. These are characterized as structural alterations that usually call for medical intervention and have a major impact on the affected person’s health, appearance, or social life. Spina bifida and cleft lip are two examples.

Structural congenial anomaly

The majority of congenital anomaly-related mortality, morbidity, and disabilities are caused by major structural defects. On the other hand, mild congenital defects are structural alterations that do not offer a considerable health risk during the neonatal period and typically have minimal social or esthetic ramifications for the affected individual, although being more common in the population. Clinodactyly and a single palmar crease are two examples.

In order to encourage nations to create internal capacity for the creation of congenital abnormalities surveillance systems, the prevention of congenital anomalies, and the raising of awareness about their impact, the 63rd World Health Assembly adopted a resolution on congenital anomalies (2) in 2010. The resolution requests that Member States conduct screening programs, work toward preventing congenital anomalies wherever feasible, and offer continuing support and care to children and their families who have congenital anomalies. WHO’s role is to enhance research and data collecting in this field and assist Member States in putting these services into practice.

Types of congenital anomalies

There are two categories of structural congenital malformations: major anomalies and minor defects. It is occasionally possible for one person to have both major and minor anomalies.

Major anomalies

Major abnormalities are structural alterations that usually demand for medical intervention and have a major impact on the affected person’s social, medical, surgical, or cosmetic outcomes. Anencephaly, cardiac abnormalities, spina bifida, and orofacial clefts are a few examples. The majority of congenital anomaly-related death, morbidity, and disability are caused by major malformations.

Minor anomalies

Small irregularities are structural alterations that present little to no risk to health and typically have minimal social or cosmetic repercussions for the afflicted person. Identifying syndromes can be aided by minor anomalies, which are more prevalent than big anomalies. A single palmar crease and clinodactyly, or the moderate curve of a finger, are two examples of minor malformations.

Risk factors for congenital abnormalities

Risk factors for congenital abnormalities include:

- genetic factors;

- maternal diseases (e.g. diabetes and obesity);

- maternal age;

- Behaviours and environmental exposures that may put a woman at risk for having a pregnancy impacted by a congenital abnormality.

Risk factors associated with congenital anomaly

Potential reactions:

- nutritional inadequacies or deficits (e.g. folate)

- Mother’s age

- disorders affecting mothers (e.g., diabetes, hypothyroidism)

- infectious disorders (such as syphilis and rubella)

- misuse of alcohol

- Being overweight

- Use of tobacco

- Some drugs

- Pollution of the environment (e.g. pesticides)

- low social standing

- ancestry

- genetic components

Compared to other children her age, as well as suffer major health issues (e.g. Down syndrome).

Prevention from congenital anomaly

Potential reactions:

- Obtain current immunizations before becoming pregnant

- Sustain a healthy weight

- Before becoming pregnant, make sure you are getting enough micronutrients, such as folic acid, via vitamin supplements or fortified foods.

- Before getting pregnant, manage your diabetes

- To prevent hypothyroidism, take iodine.

- Avoid smoking and excessive alcohol use before and during pregnancy.

- Consult a healthcare professional on the usage of any medications.

Congenital anomaly causes

Roughly 25% of all congenital abnormalities are thought to have a genetic origin (45). More recent estimates, however, indicate that the percentage may be greater because, over the past 20 years, developments in cytogenetic and molecular procedures have made it possible to identify chromosomal abnormalities, gene mutations, and genetic polymorphisms that were previously undiagnosed. Single-gene defects and chromosomal abnormalities are the two most prevalent genetic causes of congenital malformations.

Gene structural alterations, or mutations, are the source of single-gene problems. Slightly more than 17% of congenital abnormalities are caused by these (48). Single-gene defects can result from a spontaneous (new) mutation or be inherited from one or both parents. While new research is increasingly identifying single-gene defects that cause isolated anomalies, such as cleft lip with or without cleft palate and some types of congenital heart defects, single-gene mutations appear to be more frequently linked to multiple syndromic congenital anomalies than to isolated malformations.

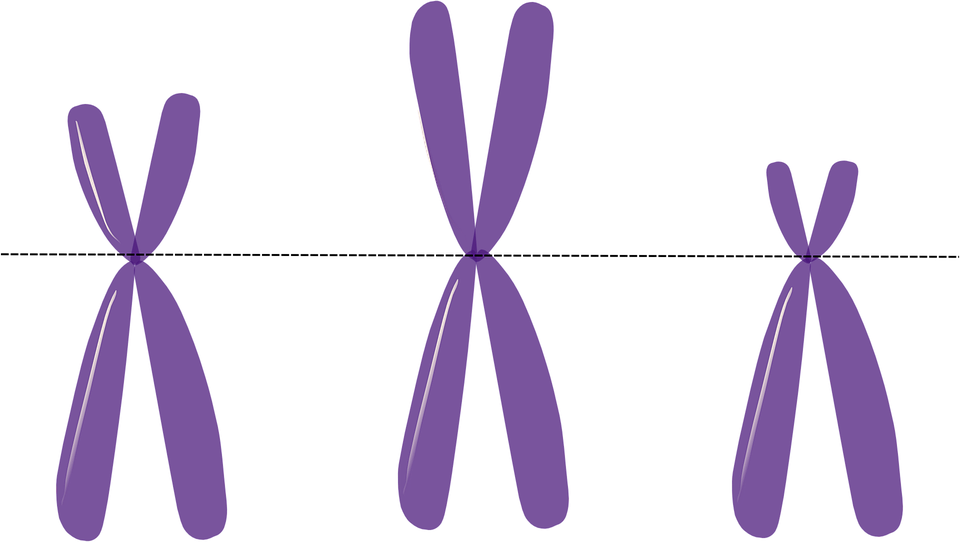

chromosomal alterations

10% of children with congenital malformations have abnormalities due by chromosomal alterations, which might affect the sex or autosomes (48). Chromosome structural abnormalities include deletions (e.g., duplication of the short arm of chromosome 9), duplications of the long arm of chromosome 22 associated with the DiGeorge and velocardiofacial syndromes, and extra chromosomes (e.g., trisomies such as Down syndrome or trisomy 21, trisomy 13 and trisomy 18) or missing chromosomes (e.g., monosomies such as monosomy X or Turner syndrome). Multiple congenital anomaly patterns are usually often linked to chromosomal disorders.

An estimated 4–10% of congenital abnormalities are caused by known environmental and maternal factors (49). As examples, consider:

- mother’s nutritional state,

- chemical exposure, and potential use of illegal drugs

- infections in mothers (such as rubella)

- physical elements, including heatstroke and ionizing radiation (49) chronic illnesses in mothers (such as diabetes)

- Exposure to known teratogenicity prescription drugs (e.g., valproic acid, retinoic acid); see the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists’ fact page (50) for additional information on medications.

Multifactorial

The etiology of about 66% of congenital abnormalities is still unknown (49). This category comprises congenital malformations that are thought to be complex or to have environmental origins. Multifactorial refers to the process by which an abnormality is caused by the interaction of several unknown gene variations with environmental variables.

Numerous possible relationships between the environment and also genes have been investigated in regard to various congenital abnormalities. For instance, the degree to which certain gene alterations and polymorphisms, such as those pertaining to TGFA, TGFB3, CYP1A1, NAT1, NAT2, and GSTT1, are associated with a higher incidence of oral clefts in the progeny of cigarette smokers has been investigated (51). An further instance of a gene-environment interaction is when phenytoin, a common anticonvulsant medication, is exposed to a developing embryo. In 3–10% of infants exposed to phenytoin while still in utero, structural congenital abnormalities are linked to the treatment.